Authority: The Real Challenge of the Synod (3)

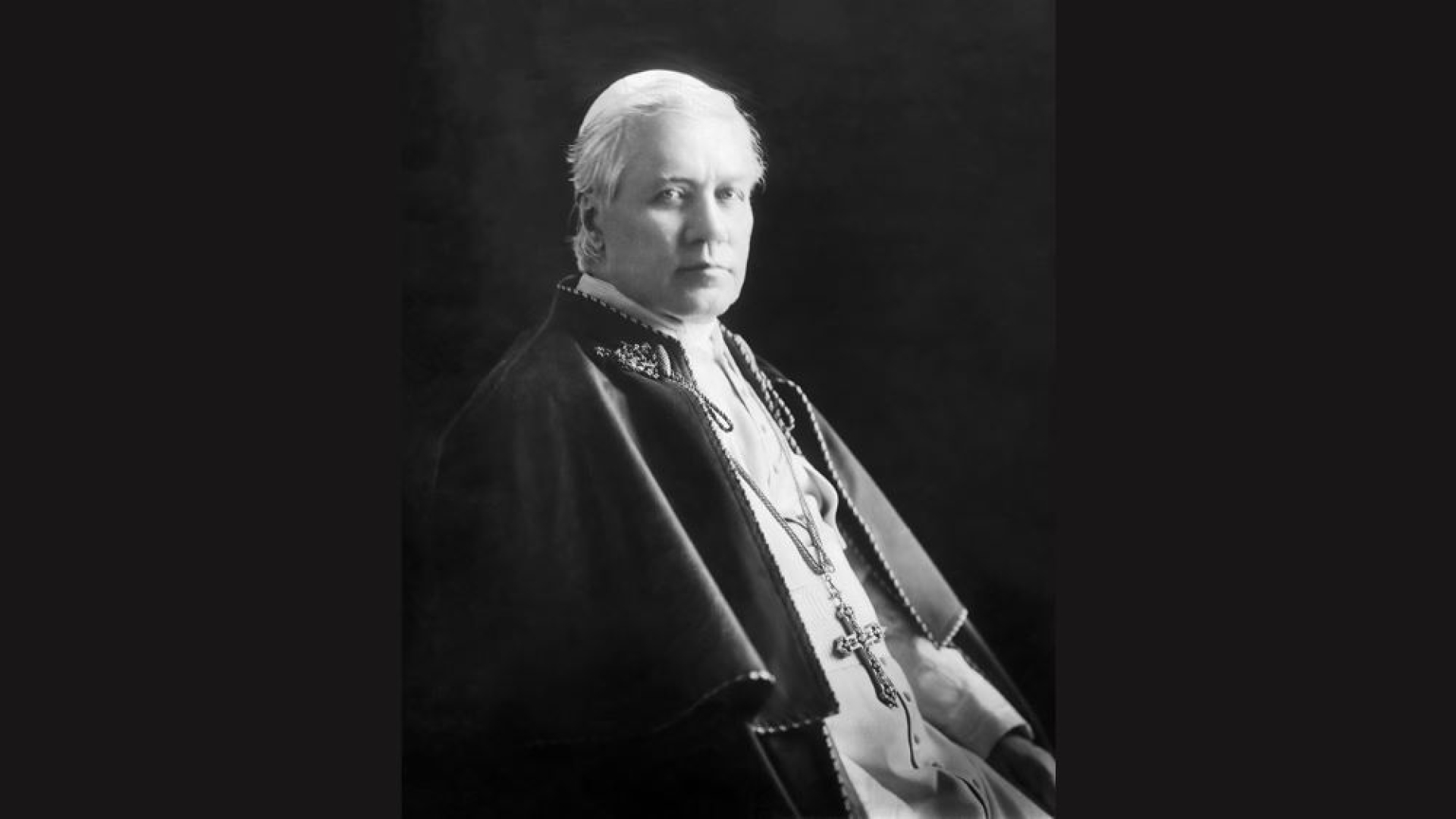

St. Pius X (circa 1914)

What is authority, according to Vatican II? “One party in power and all the others in prison,” once said Mikhaïl Tomsky (1880-1936), who was a revolutionary trade unionist then member of the Politburo in the USSR under Stalin. The following is by Fr. Jean-Michel Gleize, SSPX.

1. “The injustice of an act when successful inflicts no injury on the sanctity of right.” This condemned proposition, the 61st of the Syllabus of Errors of Pius IX, describes well enough the pastoral approach of Pope Francis—at least, in any case, inasmuch as it does not wholly forbid the practice of admitting public sinners to the reception of the Holy Eucharist. Perhaps soon there will be blessings of LGBT unions?

We could also draw a parallel between this proposition of the Syllabus and the recent deposition of Bishop Joseph Strickland. But already, in 1976, the confused and bewildered Catholic had been able to see the condemnation of a “wild Seminary,” the Seminary of Ecône, where Archbishop Lefebvre, the former Archbishop of Dakar, did nothing but apply the decrees of the holy Council of Trent.

A Change in the Definition and Nature of Authority

2. This manner of exercising authority corresponds to a change in definition of the very nature of authority. Indeed, if it sanctions and decrees a fact, it is because it is the expression of brute Numbers, the will of a majority. Authority then becomes what it is in Rousseau’s Social Contract—that is to say, the expression of the general will. It also becomes what it is in modernism—that is to say, the expression of the common Conscience of the People of God.

3. The common good is thus no longer, in the modernism of Vatican II, exactly what it was until this point, in the doctrine of the Church, based on the explanation that Aristotle and St. Thomas gave of it. For them, the common good is the End—that is to say, the first cause on which all the rest depends and in view of which all the rest must be organized.

And this End, this cause, is firstly the transmission of the deposit of the Faith, the expression of the double divine law—natural and revealed—to which men must conform their actions if they want to obtain the eternal salvation of their souls. With Vatican II and Francis, the common good is itself a “universal Fraternity”—that is to say, a communion desired for its own sake, or rather desired as the sign of hope for the unity of the whole human race.

It is not an End but a sign—or a sacrament. The Pastoral Constitution Gaudium et spes indeed asserts that “this sacred synod, proclaiming the noble destiny of man and championing the Godlike seed which has been sown in him, offers to mankind the honest assistance of the Church in fostering that brotherhood of all men which corresponds to this destiny of theirs” (Preface, no. 3).

As a result, the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen gentium defines the Church as a “messianic people”—that is to say, “a lasting and sure seed of unity, hope and salvation for the whole human race,” sent “into the whole world as the light of the world and the salt of the earth” (Chapter II, no. 9).

The mission of the Church is that of a testimony, an expression of the common conscience of the People of God which expresses the needs of humanity, and it is why authority defines itself in the Church as a service, in the measure in which it sanctions this expression and assures its permanence.

Related Article

The Common Conscience as a New Source of Revelation

4. The Compendium of the Catechism of the Catholic Church published in 2005 and approved by Benedict XVI already said, incidentally, in question 15: “To whom is the deposit of faith entrusted? [...] The Apostles entrusted the deposit of faith to the whole of the Church. Thanks to its supernatural sense of faith the people of God as a whole, assisted by the Holy Spirit and guided by the Magisterium of the Church, never ceases to welcome, to penetrate more deeply and to live more fully from the gift of divine revelation.”

This is a Revelation which identifies itself with the common Conscience, rebaptized as the “supernatural sense of faith.” The Compendium here takes up again no. 91 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church: “All the faithful share in understanding and handing on revealed truth. They have received the anointing of the Holy Spirit, who instructs them and guides them into all truth.”

And in the Apostolic Exhortation Verbum Domini, which in 2010 drew conclusions from the Synod of 2008, Pope Benedict XVI also declared that “His [God’s] word engages us not only as hearers of divine revelation, but also as its heralds” [1]. The document later continues, “Since the entire People of God is a people which has been ‘sent’, the Synod reaffirmed that ‘the mission of proclaiming the word of God is the task of all of the disciples of Jesus Christ based on their Baptism.’

“No believer in Christ can feel dispensed from this responsibility which comes from the fact of our sacramentally belonging to the Body of Christ. A consciousness of this must be revived in every family, parish, community, association and ecclesial movement. The Church, as a mystery of communion, is thus entirely missionary, and everyone, according to his or her proper state in life, is called to give an incisive contribution to the proclamation of Christ” [2].

5. In the Intervention which he delivered during the Synod, on Wednesday, October 25, Pope Francis returned to this idea, in terms full of imagery only he could interpret: “I like to think of the Church as this simple and humble people walking in the Lord’s presence (the faithful people of God). [...]

“One of the characteristics of this faithful people is its infallibility; yes, it is infallible in credendo [in belief]. (In credendo falli nequit, says LG 12). Infallibilitas in credendo. [Infallible in belief.] An image comes to mind: the faithful people united at the entrance of the Cathedral of Ephesus.

“History says (or legend) that the people were on both sides of the street leading to the Cathedral while the Bishops entered in procession, repeating in chorus: “Mother of God”, asking the Hierarchy to declare as dogma this truth that they already possessed as the people of God. (Some say they had sticks in their hands and were showing them to the Bishops).

“I don’t know if this is history or legend, but the image is valid. [...] The members of the Hierarchy come from this people, and we have received the faith from this people, generally from our mothers and grandmothers — ‘your mother and your grandmother’ Paul says to Timothy.” Thus, on this point, Francis continues the ideas of Benedict XVI, and the Synod of 2023-2024 is in a line of continuity with that of 2008.

[1] Verbum Domini, no. 91.

[2] Verbum Domini, no. 94.

Related Article

The Refutation by St. Pius X

6. In the Encyclical Pascendi, St. Pius X explains very clearly what the radical principle is which results in making authority, in the Church, the spokesperson of the common Conscience. This principle is only a variation (or an adaptation) of a Protestant principle, the principle of the autonomy of the conscience—or of free examination—due to which Revelation is identified with conscience—or with the “supernatural sense of faith” or again with “anointing of the Spirit.”

If divine Revelation (that is to say, the communication of the truth and of the law made by God to men) is identical to the conscience (or to a realization), then authority in the Church logically becomes the voice of the conscience. Protestantism identifies Revelation with individual conscience and that is why it foments division and anarchy—as much intellectual as moral.

Protestants cannot neutralize this problem except at the cost of a contradiction, by reintroducing into the Church the rule of an authority that their principle of free examination renders impossible. Modernism identifies Revelation with the common Conscience, and with Vatican II the “supernatural sense of faith” or the “anointing of the Spirit” is the prerogative of all the People of God.

This variation of the Protestant theme makes possible the maintaining of authority as a principle of unity, without falling into contradiction. But it is at the price of a complete change of the definition of authority—a change which is equivalent to an inversion.

Authority no longer descends from on high; it emerges from below. St. Pius X mentions that modernists “make consciousness and revelation synonymous.” He says that such people want “the law, according to which religious consciousness is given as the universal rule, to be put on an equal footing with revelation, and to which all must submit, even the supreme authority of the Church, whether in its teaching capacity, or in that of legislator in the province of sacred liturgy or discipline.”

7. If authority, in the Church, makes itself the spokesperson of the common Conscience of the People of God, then, says St. Pius X, “To prevent individual consciences from revealing freely and openly the impulses they feel, to hinder criticism from impelling dogmas towards their necessary evolutions - this is not a legitimate use but an abuse of a power given for the public utility.” It is an abuse of authority.

We see that Pope Francis gives all liberty of expression to those whom he considers the “peripheries” of the Church and who press, justly, toward these necessary evolutions which the recent Synod wanted to highlight. And if it silences the criticism of Bishop Strickland, it is precisely because he set himself in opposition to these evolutions, and by the same fact, also in opposition to the Synod.

8. With Francis and the recent Synod, the authority of the Pope in the Church is thus very much at a crossroads.

Fr. Jean-Michel Gleize

Fr. Jean-Michel Gleize is professors of apologetics, ecclesiology, and dogma at the St. Pius X Seminary in Écône. He is the main contributor to Courrier de Rome. He participated in the doctrinal discussions between Rome and the SSPX between 2009 and 2011.

Original Article

(Source : La Porte Latine – FSSPX.Actualités)