The Holiness of the Church (4): The Virtue of Faith-2

The Virtue of Faith by Santo Varni

The manifestation of holiness in the Roman Church continues through the virtue of faith. We have seen how it manifests itself in the work of the holy doctors who exposed and transmitted revealed doctrines and refuted heresies in the most wonderful manner.

We must now consider how faith can be defended by works and how, if it is lived interiorly, it is a principle that enlighten a Christian's choices.

The Saints and the Defense of Orthodoxy

The defense of the true profession of faith is not only through study, which intellectually and theologically refutes heresy, but also through action which prevents heresy from spreading, either by preaching or by the means that divine law and natural law assign to Truth.

This is first and foremost the work of the great saints who preached against heresy with astonishing results: think of St. Francis de Sales (+1622) who brought the entire population of Chablais back to the Roman faith by his gentleness and his doctrine.

But it is also the work of the saints who fought the heretical drift with the means of justice, to preserve Catholics from the poisons of error. It is indeed the exclusive right of the Truth to be spread, while spreading error is a crime. Such propagation must, in all justice, be prevented or punished to the extent possible, in the name of the integrity of the faith.

Saints who have distinguished themselves in this struggle are not lacking. St. Peter Martyr (St. Peter of Verona) was a Dominican inquisitor killed by heretics in 1252 between Como and Milan. He had professed the Catholic faith against the Cathars since his childhood. Dying, he professed before them his faith in the oneness of God by writing “Credo in unum Deum” on the ground with his own blood.

St. Pius V himself (+1572), before becoming pope, was an inquisitor and worked with extreme zeal to put a stop to heretics spreading their errors through their preaching and their books, considering as an intolerable evil the free preaching of errors against the revealed faith.

The Spirit of Faith

The Faith, however, is not only an ensemble of truths about God to preserve and defend against speculative errors; it is also a light which allows us to see the true reality of things, even the ones that we see everyday.

We are not speaking here of coherence between our comportment and our belief, but of something more profound: if a man truly and intimately believes in invisible truths, he can no longer make his choices only on the basis of what he sees and knows with his senses.

Without, for the moment, taking into consideration the case of the martyrs, who preferred the invisible precisely because they believed it to be yet more real than the visible, thanks to their spirit of faith, we will mention the examples of saints who did not calculate in human terms, but made evaluations based on the afterlife.

In this way, a saint’s choice appeared at first to be incomprehensible to men. It often appeared to be reckless, even foolish. In some cases, however, the correctness of the saint’s choice through faith will not only appear in the afterlife or on the Day of Judgment, but already in this life or in history, so as to constitute an apologetic argument.

Several Great Examples

It was certainly the spirit of faith, and not only theology, that allowed St. Pius X to see not only the modernists’ errors, but the extreme danger the Church risked in tolerating them or in considering them as a secondary trend, as they began to spread among ecclesiastics.

This is why even men of sane doctrine could not understand the severity of the sainted pontiff towards the modernists: they did not lack faith but the spirit of faith.

St. Clement Hofbauer (1750-1820), a man of modest origins and without financial means, quit the Vienna seminary where they taught the errors of Josephism, losing all hope of becoming a priest, and left for Rome to meet St. Alphonsus.

Even though he was not being forced to listen to these errors, he was ready to give up his vocation, despite all the efforts he made to obtain help to enter the seminary. Yet this seminary was theoretically Catholic, and he could have tolerated it and kept silent so as to be ordained: but keeping silent would have made him suspect of having accepted these ideas that the Church had condemned.

The spirit of faith pushed him to a humanly desperate choice. However, not only did he become a priest, but he also became one of the most distinguished members and orators of his congregation.

The spirit of faith is the principle of supernatural prudence and of the power of saints. It was at the heart of Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre’s choices after the Council, when he evaluated the means to defend the doctrine of the Church, not according to human considerations, which would have discouraged the undertaking, but by the way he perceived the will of God which was slowly revealed to him, by reading the events according to faith.

A prelate in the present crisis who limits himself to condemning the errors and attacking modernism, certainly shows that he wants to defend the faith; but if he does not know and cannot act concretely, he would show a lack of such a spirit, and evaluating events based on purely human terms, his action would remain paralyzed.

The sign of Catholic holiness, therefore, is not only knowing revealed doctrine, nor even the fact of defending it with good arguments, but is also and above knowing in fact what must be done in the light of the truths of the faith which the saint has profoundly received and made his own, and of doing it. This is where the most properly supernatural aspect of this virtue appears.

(Source : DTC – FSSPX.Actualités)

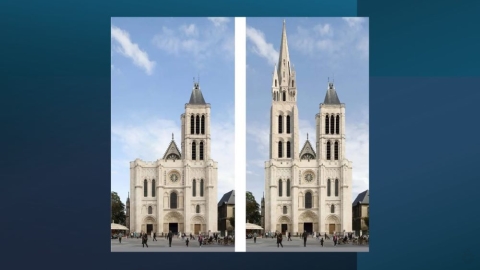

Illustration : Twice25 e Rinina25, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons