Return to the Dutch Catechism Affair (1966-1968)

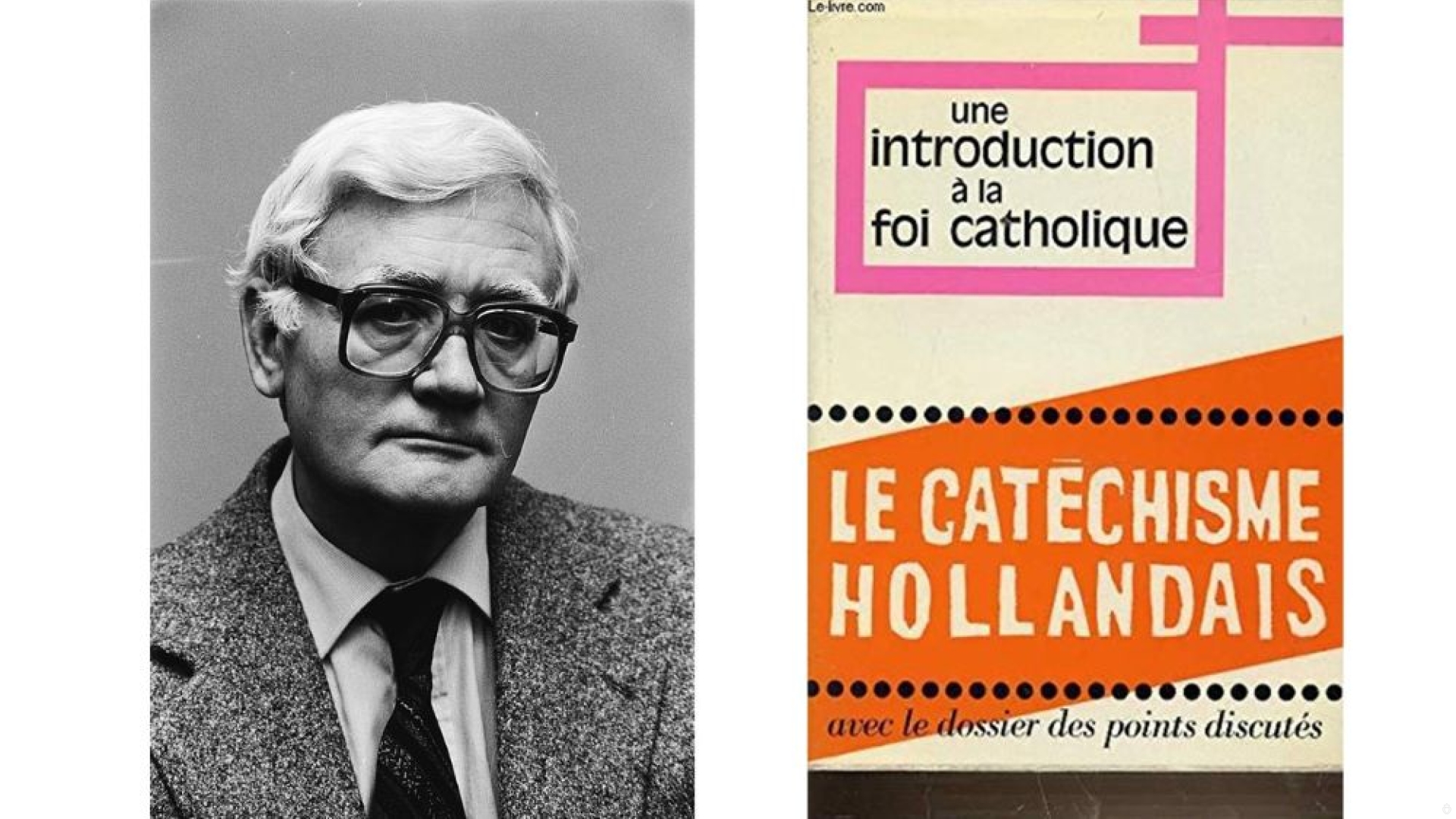

Fr. Edward Schillebeeckx and the Dutch Catechism in a French translation

It is useful to recount the affair of the Dutch Catechism, which was recalled by Bishop Peter Kohlgraf as a point of comparison with the evolution of the Church in Germany.

Background

Dutch Catholics have for a long time been known for their faith, because they have had to fight against a hostile Protestant climate since the 16th century. In the 20th century, they became the majority, with important structures, a strong identity, and numerous missionaries throughout the entire world.

But after the war, materialism transformed life. Practice--above 70%--was in decline. Since the early 1960s, the use of contraceptives spread among Dutch Catholics, resulting in a reduction in family size, the number of seminary candidates, and a diminishing of the sense of Faith. The traditional distancing from Protestants no longer made sense.

Context

Since 1956, professors of the Higher Catechetical Institute at Nijmegen had been commissioned by the Dutch episcopate to compose a catechism for children. In 1960 it was decided to make it for adults. It was published in 1966 with the imprimatur of Cardinal Bernardus Alfrink.

The direction is due to the Dutch Jesuit Piet Schoonenberg (1911-1999) and to the Belgian Dominican Edward Schillebeeckx (1914-2009), professors at the Institute. Fr. Schillebeeckx was a voice listened to at the Second Vatican Council, although he had not been named an expert.

The Origins of the Serious Shortcomings of the Catechism

The text considers the situation of the world, attempting to grasp in a positive way the different religions, including Marxism, as expressions of the search for God. It integrates the perspective of the sciences, and that of evolution. This approach was flawed.

Nevertheless, that was not the worst of it. Serious errors were exposed, the root of which lay in two underlying intentions. The first: to get along with the Protestant part of the country, trying to improve the Catholic explanations, but also avoiding what could displease the Reformed.

The second: it was about reaching the modern world. This led to the search for smooth formulas, to avoid difficult subjects (Original Sin, miracles) and to interpret other, “less credible” ones such as the Virgin conception, angels, and the Resurrection, as metaphors. The writers had become convinced that these points were not properly matters of Faith and that they were free to seek a symbolic interpretation.

Finally, the writers searched for alternative expressions to the traditional formulas of the Faith, substituting “philosophical” terminology. This led to difficult and unusual reconstructions of central dogmas--the Trinity, the personality of Jesus Christ, sin, sacraments--which lost precision. The problem lies in what was not affirmed or what was reinterpreted.

Catholic Opposition

Opposition immediately arose from well-formed Catholics. They exposed the shortcomings in a newspaper (Confrontatiie) and sent a letter to the Pope, published in the Catholic press (De Tijd). The writers of the catechism reacted very badly.

Paul VI then appointed, in agreement with Alfrink, a mixed commission of three Roman theologians (Edouard Dhanis, Jan Visser, Benedict Lemeer) and three members of the Institute of Nijmegen (Schoonenberg, Schillebeeckx, and W. Bless). They met at Gazzada (Italy) in April 1967, but the delegation of the Institute refused any change, on principle.

The Commission of Cardinals

Paul VI then appointed a commission of six cardinals (June 1967): Josef Frings, Joseph-Charles Lefebre, Lorenz Jaeger, Ermenegildo Florit, Michael Browne, Charles Journet. They would be assisted by seven theologians. The list of points to correct or clarify is long:

The existence of angels and demons, the immediate creation of the soul by God, Original Sin, polygenism, the Virginal conception of Christ, the perpetual virginity of Mary, the expiatory satisfaction of the sacrifice of the Cross, the perpetuation of the sacrifice in the Eucharist, Transubstantiation, the Real Presence, the infallibility of the Church, ministerial priesthood and common priesthood, the primacy of Rome, knowledge of the Trinity, the divine consciousness of Jesus, baptism, the sacrament of Penance, miracles, death and resurrection, judgment and Purgatory, the universality of moral laws, the indissolubility of marriage, birth control, venial and mortal sins, and the married state.

The commission published a Declaration (October 15, 1968), indicating the necessary corrections and additions. As Omnes reports, “The Insitute refused to correct the text and promoted translations into German, French, English and Spanish, without rectifications or nihil obstat [...] [T]hey were sure that their proposal was the future of the universal Church and they were ready to defend it at any cost.

“It was then decided to convert the corrections into a Supplement of about 20 pages, which could be added to the unsold volumes of the various editions and translations, with the approval of the publishers.”

Related Article:

Influence of the Dutch Pastoral “Council”

This “council,” begun in 1966, was influenced by the errors of the Dutch Catechism. In particular, the third session (1969) was very much affected by the climate created by the question of the Catechism and by the tension with Rome which resulted from its examination and then the Declaration of the Commission of Cardinals.

This partially explains the excesses that this “council” examined then voted on with the blessing of the Dutch episcopate.

Paul VI, at the request of Jacques Maritain and Cardinal Charles Journet, who prepared the framework of the text, reacted with the publication of the Credo du peuple de Dieu, solemnly proclaimed at the Vatican on June 30, 1968, for the closing of the Year of Faith. The Pope essentially reaffirmed the truths of the Faith denied or questioned by the Dutch Catechism without naming it.

(Sources : CNAd/InfoCatolica/Omnes/Wikpédia – FSSPX.Actualités)

Illustration : Hans van Dijk for Anefo, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons