The Holiness of the Church (10): The Virtue of Religion

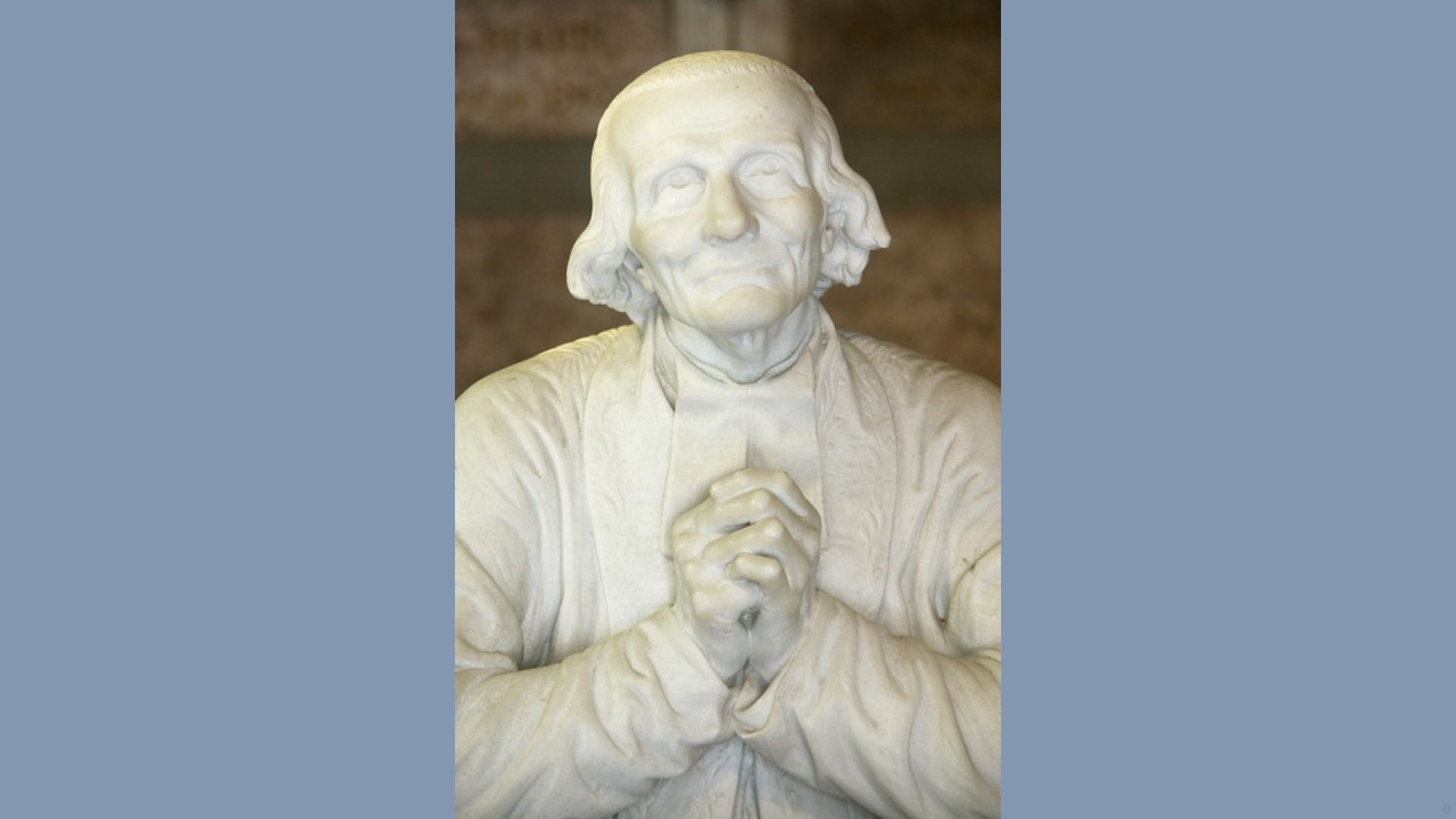

St. John Vianney, the holy Curé of Ars praying by Emilien Cabuchet

Linked to the virtue of justice, the virtue of religion shares with it the need to pay a real debt, but this time to God Himself. This virtue is distinguished from justice in the strict sense precisely because of the impossibility of rendering equally what one owes to God.

Religion therefore inclines man to render the worship which is due to God, our Creator and Lord and the supreme principle from which we have come. Religion can be considered a general virtue: indeed, any good deed can be transformed into an act of worship to God, by which we offer something of ourselves to the Divine Majesty.

Such virtue permeated the lives of the saints. Certainly, unlike the theological virtues, it does not have God as its direct object: nevertheless, God is its mediate object, precisely through the acts of worship imposed by religion. These acts are often acts of faith, hope, and charity. We then understand the preeminent role of this virtue over the other moral virtues.

The Main Acts of Religion: Devotion, Prayer, and Adoration

Devotion is the will to give oneself to what amounts to divine service. Our Lord was the first example: “My meat is to do the will of Him that sent Me” (Jn. 4:34). Since charity disposes us to give ourselves to God, devotion directly concerns the works of divine worship, which the saints performed with zeal, fleeing from acedia – the vice opposed to devotion.

The devotion of the saints is manifested by their readiness to perform acts of adoration, to devote time to prayer, and through the manner in which they perform the outward gestures of prayer. St. Louis de Gonzague spent the night, even in the middle of winter, dressed in his tunic, on his knees or prostrate, in the contemplation of celestial things: thanks to this constancy, he had the gift of stability of mind in prayer, without any distraction, like a kind of perpetual ecstasy.

Prayer or contemplation was the principal activity of all the saints, under all its forms: liturgical and public, personal, of intercession, or of thanksgiving. As for the liturgy, it was the saints – above all the Fathers of the Church and the great founders of monastic orders – who regulated it and who left us this treasure that constitutes the various traditional rites.

The subject of the saints’ work in liturgical matters deserves a treatment in its own right, and would make even more absurd the claim of making a tabula rasa of such a heritage, a claim made in the time of Paul VI.

It is hardly possible to measure the time the saints spent in prayer: on the apologetic level, it suffices to show how their prayers of intercession, united with the divine will, obtained miraculous results. The prayer of St. Stephen, the first deacon, obtained the conversion of St. Paul; that of St. Gregory the Wonderworker moved a mountain that hindered the building of a church, literally fulfilling what is promised in the Gospel (Mk 11:23).

As for worship or adoration, if it is somehow included in the acts of prayer themselves, it also manifests itself specifically in particular acts of worship. We must mention in particular the adoration that the saints showed towards the Blessed Sacrament: the great theologian St. Thomas Aquinas sought wisdom in it; St. Pascal Baylon consecrated his life to the adoration of the Host, to the point of opening his eyes during his funeral at the elevation of the Host, as a sign of adoration.

Vows

Another part of this virtue is the vow, by which a good deed also becomes an act of religion, by a promise made to God. In particular, the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, or vows of religion, consecrate the whole man and his actions to divine worship, by fulfilling the evangelical counsels.

The man who has promised God to give up his earthly appetites and even his own will becomes in some way sacred. Religious life, founded on the words of Christ, is one of the signs of the divinity of the Catholic Church and it was the saints who spread and established it.

All the great religious orders, as well as most of the congregations, were founded by saints: men wanted to consecrate themselves to God by following the example and rule of these great figures. The rule of St. Benedict is the consecration of man and time to divine worship, making the monk a being entirely devoted to the work of the liturgy.

The Rule of St. Francis, like its author, detaches man from the appetite for earthly goods in the most radical way possible, to make it a constant offering to God. The special vow of obedience to the Pope by the Jesuits makes their life a gift to the common good of the Church, seen from the highest angle.

All religious life includes the vow of chastity, that is, consecration to God of what is deepest in man, and what is most disorderly after original sin: the appetite that drives generation. Chastity, of which we will speak in the chapter on temperance, thus becomes the means of offering to God an entire victim, of making the most total offering in itself.

This vow is common to all who consecrate themselves to God, beginning with the holy virgins of antiquity, often put to death for refusing marriage after offering themselves to God.

The Fight Against Impiety and Irreligion

One cannot describe the virtue of religion of the saints without mentioning their hatred of the sins which go against this virtue: superstition, magic, blasphemy, simony, and sacrilege.

From antiquity, we see martyrs urged by the Holy Ghost against pagan superstitions, knowing that it would cost them their lives. Some of them rose up to pull down the statues of idols: like St. Blaise, Bishop of Sebastea, who not only refused to worship idols, but overthrew them.

St. Benedict, at Monte Cassin, demolished the temples of Apollo and Jupiter and erected churches in honor of St. Martin and St. John the Baptist. In the letters of St. Gregory the Great to St. Augustine of Canterbury, sent to evangelize the Anglo-Saxons, there are many recommendations to burn pagan idols and build churches in their place.

From England, St. Boniface traveled to Germany with the blessing of the Pope, to evangelize the Saxons, who were still pagans. One day he went to a village and preached the Trinity. The elders having answered him that the God of Boniface was “invisible” whereas their oak Odin was much more real, St. Boniface felled the oak with an axe, saying to them: “Where is your god now?” It is with oak wood that the cross erected on the village church was built.

In the same spirit, St. Gregory VII or the martyr deacon St. Arialdo fought against simony and Nicolaism: they wanted worldly appetites to stay away from the altars, dedicated solely to divine worship. The fight of St. Bernardin or St. Leonard of Port-Maurice against blasphemy also stems from religious zeal.

Simony consists in selling the sacraments, in performing them only for a fee. The name comes from Simon the magician who asked St. Peter to “sell” him his powers. Nicolaism is when a cleric obliged to chastity – beginning with the receipt of the order of the sub-diaconate – is living in a marital relationship.

Related links

(Source : Somme théologique – FSSPX.Actualités)

Illustration : Photo 232732614 © Pascal Deloche | Dreamstime.com