The Grace of a Good Death

The end of the liturgical year is the occasion for the Christian, in the mind of the Church, to meditate on his final end, and in particular on the preparation for a good death. At a time when the end of life is being hastened by euthanasia, it is helpful to highlight this very special grace called final perseverance.

Can We Deserve the Grace of a Good Death?

Final perseverance or a good death is nothing other than the continuation of the state of grace until the moment of death; or at least, if one converts at the last moment, it is the conjunction of the state of grace and death. In short, a good death is death in a state of grace.

This state of grace at the moment of death allows man to take part personally in the acquisition of his eternal happiness. It is because he perseveres to the end in friendship with God that God, by virtue of this friendship, introduces him to his heavenly reward. The man then in reality merits this reward: “Good and faithful servant, you have been faithful in a few things, enter into the joy of your Master.”

But if the happiness of Heaven is thus merited by perseverance in the friendship of God, can this perseverance itself be merited in its turn, in the proper sense of the word merit, which implies a certain right to obtain this grace? Can we gain Heaven by merit?

St. Thomas Aquinas responds with finesse: the principle of merit cannot be earned; for a cause, whether physical or moral like merit, cannot cause itself. If therefore friendship with God at the time of death is what allows us to merit Heaven, it cannot be merited itself.

We understand why the Second Council of Orange declared that it was a special gift, and why the Council of Trent affirmed its perfect gratuity by saying: “this great gift can only be obtained from Him alone who can preserve in good he who is standing, and who can raise him who has fallen.” This is what it is all about: to be preserved or restored to the state of grace at the time of death. It is a grace which therefore cannot be earned, and which really depends totally on God.

What we have just seen, in a certain way, is formidable; what remains to be said, on the contrary, is very consoling.

How Can the Grace of a Good Death Be Obtained?

If the gift of final perseverance cannot strictly speaking be merited, it can and must be obtained by prayer, which is not addressed to the justice of God, as merit, but to His mercy.

Prayer can indeed sometimes obtain goods by simple request, without deserving them. For example, a sinner who is not in a state of grace can, by inspiration from God, ask to find sanctifying grace, and thus be granted it. He could not then have merited this grace, since without it there is no possible merit.

It is the same with the grace of final perseverance. Strictly speaking, we cannot merit it, but we can obtain it by prayer, for ourselves and even for others. We can also, and we must even prepare ourselves to receive it, by living a better life. Very often, we die as we have lived.

This is why Our Lord taught us to say in the Pater: “Lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil.” And the Church has us say each day: “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death. Amen.”

One question remains unanswered: can we through prayer infallibly obtain this grace of a good death?

Theology, relying on the promise of Our Lord, namely “Ask and you shall receive,” teaches us that prayer made under certain conditions infallibly obtains for us the goods necessary for salvation, and consequently the last grace. But what are these conditions of infallibly effective prayer? St. Thomas tells us that there are “four conditions: one must ask for oneself the goods necessary for salvation, with piety and perseverance.”

We indeed obtain more surely what we ask for ourselves than what we implore for a sinner, who perhaps resists grace when we pray for him. But even in asking for ourselves the goods necessary for salvation, prayer is infallibly effective only if it is done with piety, humility, confidence, and perseverance. Only in this way does it express a sincere, deep, and uninterrupted desire of our hearts.

And here reappears, with our fragility, the mystery of grace. We can lack perseverance in prayer, as in meritorious works. And this is why the priest says at Holy Mass before Communion: “Do not allow, Lord, that we ever part from you.”

Let us, therefore, abandon ourselves with confidence and love to infinite mercy. This is the surest way to obtain mercy when it bends down to us, at this moment and at the very hour of our death.

In this surrender, we will find peace. When the Savior died for us, in His holy soul was united the deepest suffering, caused by our sins, and the deepest peace. Likewise, in every Christian death, as in that of the Good Thief, there is a very intimate union of holy fear, of trembling before the infinite Justice, and at the same time of profound peace, in the certainty offered by hope, that the mercy of God opens its arms to us.

It is then peace that dominates, as Our Lord said in dying: “Consummatum est ... Father, into Thy hands I commend my spirit.”

Comment la grâce de la bonne mort peut-elle être obtenue ?

Si le don de la persévérance finale ne peut être à proprement parler mérité, car le principe du mérite ne se mérite pas, il peut et doit être obtenu par la prière, qui s’adresse non pas à la justice de Dieu, comme le mérite, mais à sa miséricorde.

La prière peut en effet obtenir parfois des biens par simple demande, sans les mériter. Par exemple, un pécheur qui ne serait pas en état de grâce peut, par une inspiration de Dieu, demander de retrouver la grâce sanctifiante, et être ainsi exaucé : il ne saurait alors avoir mérité cette grâce, puisque sans elle il n’y a pas de mérite possible.

Il en est de même de la grâce de la persévérance finale : nous ne pouvons pas à proprement parler la mériter ; mais nous pouvons l’obtenir par la prière, pour nous et même pour d’autres. Nous pouvons aussi, et nous devons même, nous disposer à la recevoir par une vie meilleure : car bien souvent, on meurt comme on a vécu.

C’est pourquoi Notre-Seigneur nous a appris à dire dans le Pater : « Ne nous laissez pas succomber à la tentation, mais délivrez-nous du mal ». Et l’Eglise nous fait dire tous les jours : « Sainte Marie, Mère de Dieu, priez pour nous, pauvres pécheurs, maintenant et à l’heure de notre mort. Ainsi soit-il. »

Une question demeure en suspens : pouvons-nous par la prière obtenir infailliblement cette grâce de la bonne mort ?

La théologie, s’appuyant sur la promesse de Notre-Seigneur : « Demandez et vous recevrez », nous enseigne que la prière faite en certaines conditions nous obtient infailliblement les biens nécessaires au salut, et par suite la dernière grâce. Mais quelles sont ces conditions de la prière infailliblement efficace ? Saint Thomas nous dit qu’il y a « quatre conditions : il faut demander pour soi les biens nécessaires au salut, avec piété et persévérance ».

Nous obtenons en effet plus sûrement ce que nous demandons pour nous que ce que nous implorons pour un pécheur, qui résiste peut-être à la grâce au moment où nous prions pour lui. Mais même en demandant pour nous les biens nécessaires au salut, la prière n’est infailliblement efficace que si elle est faite avec piété, humilité, confiance et persévérance. Ainsi seulement elle exprime un désir sincère et profond, non interrompu de notre cœur.

Et ici reparaît, avec notre fragilité, le mystère de la grâce : nous pouvons manquer de persévérance dans la prière, comme dans les œuvres méritoires. Et c’est pourquoi le prêtre dit à la sainte messe avant la communion : « Ne permettez pas, Seigneur, que nous nous séparions jamais de vous. »

Abandonnons-nous donc avec confiance et amour, à l’infinie miséricorde : c’est le plus sûr moyen d’obtenir d’elle qu’elle s’incline vers nous, en ce moment et à l’heure même de notre mort.

Dans cet abandon nous trouverons la paix. Lorsque le Sauveur mourait pour nous, en sa sainte âme s’unissaient la plus vive souffrance, causée par nos péchés, et la paix la plus profonde. De même, dans toute mort chrétienne, comme en celle du bon larron, il y a une union très intime de sainte crainte, de tremblement devant l’infinie Justice, et en même temps de paix profonde, dans la certitude, offerte par l’espérance, que la miséricorde de Dieu nous ouvre les bras.

C’est alors la paix qui domine, comme en Notre-Seigneur mourant : « Consummatum est [...] Père, en vos mains je remets mon esprit. »

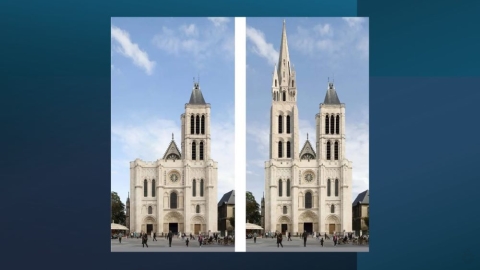

Image : © José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro