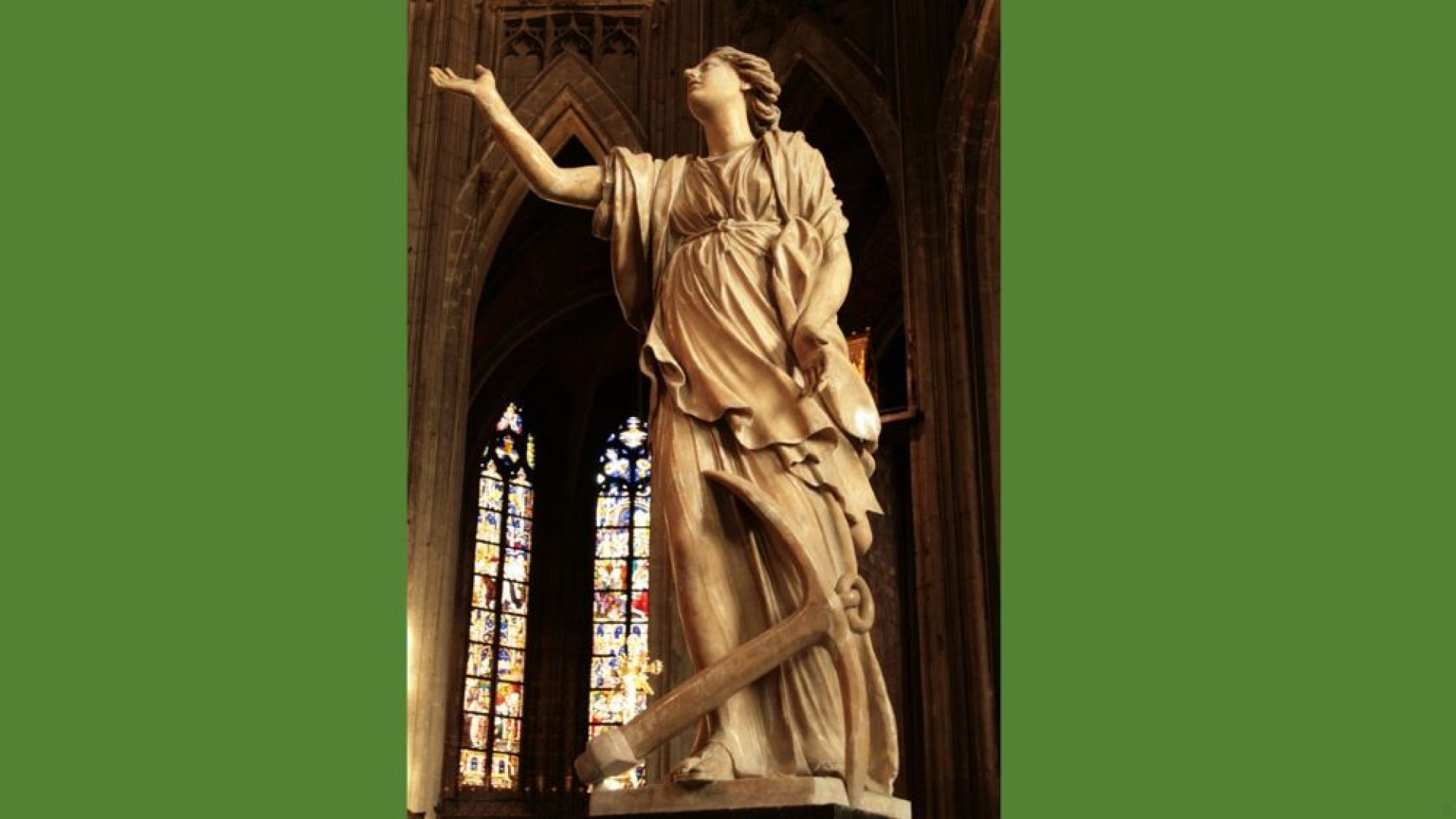

The Holiness of the Church (5): The Virtue of Hope

The Virtue of Hope

Hope, the second theological virtue, has God as its object: if faith has God as its object insofar as He reveals Himself, hope attains Him with the certain confidence of supreme felicity, and through Him all the means necessary to attain this supreme end. Hope is a Christian virtue par excellence, to the point that St. Paul speaks of unbelievers as those who “have no hope” (1 Th. 4:1).

To consider hope in the saints, it is necessary to consider the acts which proceed from this virtue, and the supernatural manifestations to which it leads the man who lives it interiorly. These acts correspond to the object of virtue: the desire for God as the only beatitude of the human soul and the confidence in the means that He alone can give, despising all the other things which come from the world and which cannot be ordered to eternal salvation.

A Heavenly Life

The saints, imbued with the virtue of hope, already manifest in this life a love for the things of heaven, a confident expectation of eternal happiness which almost constantly occupies their minds. St. Philippe Néri kept repeating: “Paradise, paradise!” as if it were the thought that constantly occupied him.

Earthly realities, honors, thus became unimportant to him: to the proposal of ecclesiastical dignities, he could only reply: “I prefer Paradise,” as if nothing on earth seemed worthy of being desired in the face of this beatitude. And St. Francis of Assisi was ready to endure any pain for this eternal reward: “So great is good that I expect all pain to be pleasing to me.”

Trust in God and the Means He Provides

Hope is made concrete in the lives of the saints by the certainty that God provides them with all the means necessary for eternal salvation and for the accomplishment of the mission that God entrusted to them as the way of salvation.

Thanks to this confidence, the martyrs were able to face torments, even when their nature was weak. In the martyrdom of St. Felicity, we read that the saint complained of the pains of childbirth, when she was already destined for torture. One of the guards scoffs, “If you complain now, what will you do when we throw you to the beasts?”

The saint replied confidently, hoping for the grace of martyrdom: “Now it is I who suffer; but then there will be another in me who will suffer in my place, and I will suffer for Him.” There was no fear or despair in such a response, but confidence that the Heavenly Father would not abandon his children.

It was also a high hope that led Mary Magdalen to her repentance, because she saw that the Lord could only grant her forgiveness for her sins; just like that of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus, who, despite her innocence, saw in God a Father who accompanies his children towards holiness, she described Jesus’s arms as being “the elevator which must raise me to the heavens.”

The two saints did not see in themselves, in their own merits or demerits, the reason or the obstacle to salvation, but entrusted themselves to divine omnipotence.

Hope as a Motive for Missionary Zeal

In the Summa Theologiae II-II, q. 17, a. 3, St. Thomas Aquinas asks if hope can have as its object the salvation of our neighbor, in addition to our own. He replies that if, in an absolute sense, hope concerns the obtaining of a good that is very difficult to attain for oneself, in another sense, the union that love brings about makes it possible to hope for good for others as well as for oneself.

This profoundly Christian conception pushed the holy missionaries and educators to expend themselves for the salvation of their neighbor, understanding that God wanted them to be intermediaries in the salvation of others.

It is not necessary to recall here how the apostles and the great missionaries gave themselves to the salvation of their neighbor, leaving all earthly security behind them. The example would be too easy. They hoped that God would save those they loved, to whom they were already united by the desire to share the same eternal good.

If we consider the saints who have done great works for their neighbor, without relying on human helpers, we find the same concept. The liturgy applies to St. John Bosco the words that St. Paul uses for Abraham: “Against all hope he believed in hope, so that he became the father of many nations.”

When the Piedmontese saint understood that he had to be the instrument of salvation for his young people, he did not doubt for a moment that God would give him all the means to accomplish his immense work, even if, on the human level , he had no “hope,” no means or power.

It is not a question here of a simple “trust in Providence,” but of a real hope, because all these goods (including material goods) which the saint needed were considered as so many means towards eternal salvation, and were part of the very object of theological virtue.

This is why, for him as for many others, God saw that they lacked nothing of what they needed for their mission, which was to sanctify them and others.

Hope and Poverty

The virtue of hope, which is placing all one's trust in God, can only engender the spirit of poverty and detachment from the goods of this world, which are considered superfluous, if not a real obstacle to salvation, according to the Gospel warnings.

There is no saint who did not despise material goods, even when he made legitimate use of them (especially for the good of his neighbor). The evangelical preference for poverty stems precisely from the impossibility of being satisfied by limited earthly goods when the object of our desires is the infinity of God.

The voluntary poverty of the saints is the clear sign of those who rely on God Himself for their daily sustenance, as the Gospel says: “Therefore I say to you, be not solicitous for your life, what you shall eat, nor for your body, what you shall put on. Is not the life more than the meat: and the body more than the raiment?

“Behold the birds of the air, for they neither sow, nor do they reap, nor gather into barns: and your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are not you of much more value than they?” (Mt 6:25-26). For after all these things do the heathens seek,” says Jesus, in other words, “those who have no hope.”

This is the kind of life chosen by St. Paul the hermit, who throughout his life in the desert received half a loaf of bread from a raven each day, without having to think about the next day: and when St. Anthony came to visit him, the crow brought a whole loaf of bread. This is how St. Francis or St. Alexis (who abandoned the immense riches of his father for a higher hope), St. Dominic, and St. Benedict Labre lived on alms, completely forgetting themselves in extreme poverty.

The saints do not seek any earthly good for themselves, being certain that whatever is useful for their salvation will be provided for them by God Himself, never trusting in man.

Ultimately, hope engenders total abnegation and, therefore, makes the saint strong in the very power of God, making him a credible and evident sign of this God in whom he believes.

(Source : DTC – FSSPX.Actualités)

Illustration : Jean-Pol GRANDMONT, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons