The Holiness of the Church (13): The Virtue of Fortitude and Its Related Virtues

Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Rome

After having evoked the principal and most characteristic act of the virtue of fortitude, namely martyrdom, let us see its more “ordinary” exercise. It is necessary not only in the face of mortal danger, but also in many circumstances of daily life through its components: magnanimity, munificence, patience, and perseverance.

Patience and Perseverance

“In your patience you will save your souls” (Lk. 21:19); “He who endures to the end will be saved” (Mt. 10:22). This is how Our Lord illustrates in the Gospel the importance of these two virtues, which are necessary so as to not to allow oneself to be overwhelmed by the sadness that comes from the prolongation of a present evil. Indeed, what characterizes fortitude is not only the vigor to overcome obstacles, but also (and above all) the ability to endure evils without being defeated, to the end.

If, as we have seen, patience and perseverance shine above all in overcoming the torments of martyrdom, it must also be remembered that these virtues were heroically practiced by the saints even in the face of less extreme evils and dangers, but perhaps more durable.

There is no state of life in which the saints of the Church have not exercised the most heroic patience. Let us think of St. Alfonso de Liguori, who suffered for decades from a bone disease and who never complained about it; of St. Rita of Cassia, who suffered for years from her husband’s temper in her marriage, succeeding with patience and gentleness in obtaining his conversion from a violent and factious life; of St. Thérèse of the Child Jesus, who exercised patience in the most routine things of her religious life, but in an absolutely heroic way.

St. Thérèse's relationship with a sister whom she considered particularly troublesome is well known. In the chapel, that sister constantly rapped the rosary on the pew, and the noise distracted and irritated the rest of the sisters.

Even the saint had trouble looking this sister serenely in the face, but she always tried not to show it. When she met her in the hallway, she was tempted not to pass her, but she controlled herself, looked at her and smiled. At the common washroom, the nun absentmindedly sprinkles her sisters with water: St. Thérèse would not dry herself, so as not to show her displeasure. “I expect to receive jets of holy water,” she said to herself.

In this way, St. Thérèse reversed her feelings towards her sister. The sound of the rosary in the chapel became to her as music that helps her to pray. Over time, one day, to her great surprise, the sister asked her: “Sr. Thérèse, why do you love me so much?”

Magnanimity

This aspect of fortitude impels one to undertake great works worthy of honor in all kinds of virtues or worthy of true honor, and therefore truly virtuous. True magnanimity therefore does not seek vain honors, nor riches, nor worldly pleasures, and it is therefore entirely compatible with holiness and humility.

Christian magnanimity rests necessarily on the virtue of hope, for nothing difficult and worthy of true honor can be achieved without divine aid. The saint is not content with a mediocre virtue, but aspires to practice it to its apogee. In this way, the saints wanted to practice the evangelical counsels in their fullness, and not only in their spirit.

They not only aspired to practice the spirit of the beatitudes, but they often wanted to go to the very end of the letter, so long as it was God's will for them. Not only did the saints despise riches, but they often wanted to renounce them in the most total and – as we would say today – the most extreme way.

They often wanted a life in which even necessities remained uncertain and entrusted to Providence. It is for this reason that orders of “mendicants” were born who did not even possess the goods necessary for daily life. As for chastity, many saints wanted to live it absolutely, preserving their virginity and even renouncing legitimate marriages.

They could not give up the honor of loving God with an absolutely undivided heart and an utterly mortified body, even at the cost of great penances to overcome all temptations. We know how St. Benedict, to conquer the thought inspired in him by a young girl he saw in the street, rolled himself in a thorny bush: for him, the ideal of virginity could not suffer any diminution or condescension.

And if certain saints have indeed accomplished what can be called “great exploits” (missionaries, warriors, politicians, charities), their magnanimity must be sought precisely in their love of virtue, which remains above all an interior victory.

Marcel de Corte, who saw the difficulty for Christians today to accomplish visibly great actions, in a world where there no longer seems to be room for genuine magnanimity, invoked for the future “the magnanimity of the humble,” always possible, and more and more necessary for everyone. It is in fact no longer possible to reason in terms of mediocrity in a situation like today's, where there is only room for virtue practiced with courage and heroism, even in small things (which today themselves have become arduous).

Munificence

Munificence prompts a man to moderate his love of riches, so that he does not limit himself in his spending when it comes to accomplishing great outward works. As we see, this virtue is in no way opposed to the spirit of poverty; on the contrary, it is the condition for observing this evangelical counsel, even when one has great economic means.

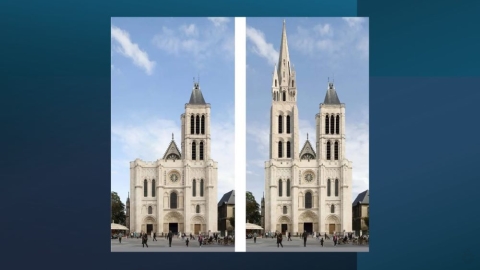

The splendor of sacred buildings and incomparable works of art (often directly desired by the saints or built in their honor), which cover Catholic countries, would in itself be a sufficient sign of the presence of such virtue in the Church. That many of the builders of these works never saw their completion rules out the idea that they could have been accomplished out of vanity.

The riches that the saints had in their hands did not remain locked up in coffers to starve the poor, but were used for works which, for centuries, have made and will make the spiritual and cultural wealth of all men, and were distributed among the workers who contributed to these enterprises.

The same applies to the wealth committed to immense works of charity and assistance, of which we have spoken above, as well as for the great war expenditures desired by the saints for the common good, such as Pope St. Pius V’s action to finance the Holy League, pledging the wealth of the Church for the victory of Lepanto, which remains decisive in the history of Christianity.

In modern times think of the St. John Bosco’s expenditures transformed into churches and schools for young people all over the world. Starting with nothing, he did not limit his projects and his achievements, but, trusting in Providence, he built without worrying about expense or limits. Just think of the Basilica of Our Lady Help of Christians in Turin or the Church of the Sacred Heart in Rome.

Work on the latter, begun by Pius IX, was stopped for lack of funds: Don Bosco accepted Leo XIII's request to complete it, but he added a boarding school and a school for poor boys to the project. Despite a business already in financial difficulty, the saint in his munificence did not want to worry about savings, and the church was quickly completed, with all its structures, rich in marble and precious works.

When, after the consecration of the church, Don Bosco celebrated Mass there for the first and only time, at the altar of Mary Help of Christians, the Mass was interrupted 15 times by the saint's sobs of gratitude.

Related links

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (11) : la piété et l’obéissance

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (10) : la vertu de religion

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (9) : la vertu de justice

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (8) : la vertu de prudence

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (7) : la vertu de charité-2

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (6) : la vertu de charité-1

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (5) : la vertu d’espérance

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (4) : la vertu de foi-2

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (3) : la vertu de foi-1

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (2) : la note apologétique

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (1) : le dogme

- La sainteté de l’Eglise (12) : la vertu de force et le martyre

(Sources : DTC/Somme théologique – FSSPX.Actualités)

Illustration : Canaan, CC BY-SA 4.0, attraverso Wikimedia Commons